Kenya N. Rahmaan

Welfare entitlements have been part of the American culture since the 1940s. And just like in nearly every other component of institutionalized governmental America, the powers that be excluded Black America from receiving public benefits. Unfortunately, misinformation constantly circulates to Black families and the welfare system. One of the most common talking points that have resurfaced applies to Black fathers being forced from their homes and children by Black mothers in exchange for welfare benefits in the 1960s. While the “man in house’ rule did exist, the talking point is not entirely accurate.

Former President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed The Social Security Act in 1935. In addition to the Social Security program, the Act included unemployment insurance, old-age assistance, aid to dependent children (ADC), and grants to the states to provide various forms of medical care (Social Security Administration or SSA). Black Americans, affectionately referred to as ‘Negroes’, rarely received any government relief in the 1930s and several decades following the implementation. Although some have argued that excluding Blacks from receiving benefits is non-racially motivated, history and recorded behavior prove otherwise.

Mothers were cared for before The New Deal and the formation of the ADC program. According to the University of Minnesota or UMN, in the early 1900s, state legislatures began to pass bills that supported single mothers called “Mother’s Pension’. Since the states operated these programs, the Federal government did not regulate administrators. The lack of governing the Mother’s Pension program meant that states could deny services and money to qualifying Black mothers. While African-Americans were more deeply impoverished, the aid was given almost solely to White women with Anglo-ancestry (UMN).

One requirement that never changed when a mother received public benefits was how she maintained the home for her children. One common requirement was that a mother maintain a ‘suitable home’ for her children (UMN). Although it’s pretty taxing to locate what a suitable home meant for recipients of Mother’s Pension benefits, it is evident what Black women had to do to comply with the suitable home requirement. The exhaustive list included mothers not having a man in the home.

The main requirement in the Mother’s Pension was that the father not reside in the home with the mother and children. In the majority of the approved cases, the father was deceased. According to Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), few states granted aid to never-married mothers or those with savings or equity in a property, even when mothers were approved for benefits. Not only were never-married parents, the government based applicant approval on whether the children were illegitimate. And these criteria disqualified White mothers, and the requirements were added to the disqualifiers reserved for Black mothers.

Black mothers were financially disadvantaged based on many reasons before becoming a widow. Employment opportunities were scarce outside of housekeeping or farming, and when welfare became involved, working became a problem. According to Baldwin ( as cited by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) (2021), Black mothers who worked for pay, many in the homes of White families, were described as proving their negligence by working late and leaving their children alone. Often, welfare was not only a necessity but an entitlement that these mothers fought to receive and would be taken quickly by caseworkers.

A ‘suitable home’ for their children was the standard that Black mothers had to comply with, which has been described as degrading and a violation of their rights. A law excluded two-parent families from receiving benefits if the state considered them both ‘able-bodied.’ Unfortunately, the fathers were absent from the home, not because they had died, but because they had to leave to provide for their families. Black men often left their families searching for work because of employment discrimination and depressed wages for Black workers (CBPP). Sadly, when the racially charged stereotypes of the Black father being kicked out of the home so that the mother can receive welfare, these realities are omitted.

When the mother miraculously received welfare benefits, the caseworkers had total control over their lives and homes. Some methods that caseworkers used to remove Black mothers from the ADC roles included:

- ‘good housekeeping ‘rules’ that allowed welfare workers to take a family off the rolls if they deemed a house to be ‘poorly maintained’ (and most houses have a few corners that could be used as Exhibit A in a white glove test),

- ‘illegitimacy’ and birth out of wedlock could cost a woman her assistance,

- and midnight raids and ‘man in the house rule’ (if caught with another man in the house, she could lose benefits) (Eastern Oregon University).

It is important to emphasize that the rule states the word ‘another’ when referring to the ‘man in the house’ law. The men that the regulation referred to were not the children’s actual fathers, but men later referred to as ‘substitute fathers. Government officials, already considering a mother’s moral integrity when awarding benefits, began questioning the male company she kept, especially if he was not her children’s father. According to the Duke Law Journal (1970), Federal government officials asked if the eligibility of most children for aid depended upon the father’s absence from the home, if the mother had a de facto husband, did not her children have a defacto father. And that is when the substitute, not the children’s father, was allegedly removed from the home because of welfare.

During this same time, most Black Americans lived in poverty due to high unemployment, low wages when they were employed, discrimination, and segregation. Even when lawmakers in D.C. passed anti-discriminatory legislation, local, state, and even the federal government did little to enforce the laws. As more Black women were applying for ADC, the government tried everything to ensure the benefit was not paid to the qualifying family. The government investigated other avenues to eliminate Black families from the welfare registers.

Alabama is paramount in how officials considered and decided welfare cases about the ‘substitute parent’ rule during the early 1960s. According to the Duke Law Journal, in 1964, Alabama submitted new state plan material under AFDC, including a ‘substitute father’ provision. Officials were convening at the Capital, discussing the future of the public welfare system during the same time. The Alabama plan required that a child was considered to have a substitute father if,

- a ‘substitute father’ lives in the home with the child’s mother for the purpose of cohabitation,

- if he frequently visits to cohabit with the mother,

- or if he does not frequent the home but cohabits with the child’s natural or adoptive mother elsewhere (Duke Law Journal).

Alabama officials wanted to control mothers from having men around them or in their homes. Federal lawmakers decided against implementing the provisions; however, Alabama enforced the unconstitutional rules into the late 1960s. A mother challenged the law after the government terminated her benefits because of the ‘man in the house’ rule. Mrs. Smith, the mother, was frequently visited by Mr. Williams, a married man with eight children. According to UNC, Mr. Williams was not the father of any of Mrs. Smith’s children and was unwilling and unable to provide for their support since he could hardly support his family. Mrs. Smith sued after being terminated because she could not afford to provide for her children on her salary as a cook.

Even though Mrs. Smith won the lawsuit, Alabama could still use the rule in certain circumstances. Specifically, the agency could terminate welfare benefits if a man living in the home had a legal, financial responsibility to the children. The challenge in Alabama led the Federal government to consider other jurisdictions and how they handled similar situations. The opinion of the Supreme Court essentially prohibited the denial of AFDC funds because of a mother’s relationship with a man who did not have a legal responsibility to support her children.

Like welfare today, the objective years ago was to decrease the number of people on welfare. Of course, when White mothers received the benefits, there was no problem, but specific rules applied when Black women were finally granted permission to receive the honor. Even though the ‘man in the house’ law was reserved for ‘substitute’ fathers does not mean that overseers of the system did not force husbands and fathers to leave homes during midnight raids. It was the 1960s, and the fight for civil rights was going strong. Black men and boys were often dragged from homes in the middle of the night for no reason.

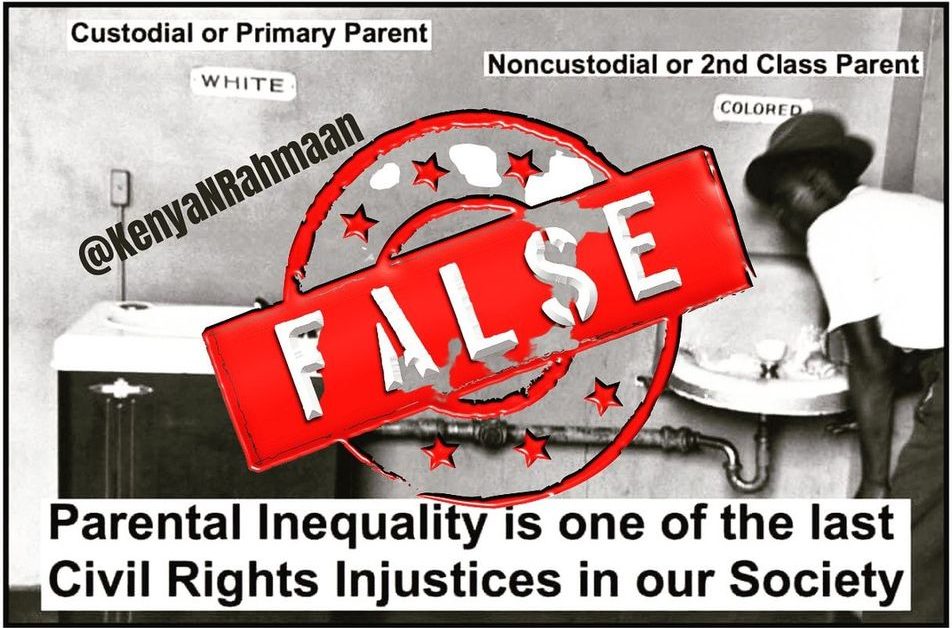

To insinuate that Black fathers overwhelmingly are absent from their children’s lives by choice without offering alternative explanations is misleading at best. When fathers of other ethnic backgrounds are missing from their children’s lives, there is an automatic assumption that they have been victims of parental alienation. However, Black fathers are not granted that same assumption. The false rumor spread is that Black fathers choose to run from their children, which is why the fatherless epidemic in America. Because the father does not reside in the home with the child does not make them fatherless. https://youtu.be/OfRU7XV1xuk

The same people who regurgitate that narrative always invoke the 1960s, the welfare system, and the racist Moynihan report. I’m here to say that Black fathers do exist and are fighting to be fathers to their children too. Black fathers are alienated and love their children too. And the myth that welfare destroyed Black families because welfare workers came in the middle of the night and forced a Black mother to kick her Black husband out is laughable. The people posting the memes and spewing the same talking points probably have never asked a Black family who lived in the 1960s about the state of the Black family.

More than likely, they refused the welfare money before they would let that happen. Here’s a thought of how the traditional Black family was ‘destroyed’ back then. So many Black people were fighting for civil rights, desegregation, equal pay, fair housing, equality, etc., that the people in charge became angry and a bit uneasy. People decided that extermination would be the best avenue even if the Black family was destroyed and children were left fatherless. And so they killed not only the Black fighter. They assassinated the Black man, father, and husband. We could start by asking the children of the Kings and the Xs’. https://youtube.com/shorts/yrCdmDRPc_w?feature=share

References:

Barrett, J. (1970). The new role of the courts in developing public welfare law. Duke Law Journal, 1, 1-23.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2021, August 4). TANF policies refthe lect racist legacy of cash assistance. Retrieved January 15, 2022, from https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance#_ftn29

Goldsmith Jr., C. F. (1968). Social welfare–The “man in the house” retthe urns state. North Carolina Law Review, 47(1), 229-235. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6271&context=nclr

Social Security Administration. (n.d.). Social security history. Retrieved January 15, 2022, from https://www.ssa.gov/history/briefhistory3.html

University of Minnesota. (2013). White privilege legislation. Retrieved from https://cascw.umn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/WhitePrivilegeLegislation.pdf

Virginia Commonwealth University. (n.d.). Social insurance & social security chronology: Part III – 1930s. Retrieved January 15, 2022, from https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/eras/great-depression/social-insurance-social-security-chronology-part-iii-1930s/

Wexler, S., & Engel, R. (1999). Historical trends in state-level ADC/AFDC benefits: Living on less and less Less and sess. The Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 26(2), 37-58. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2568&context=jssw